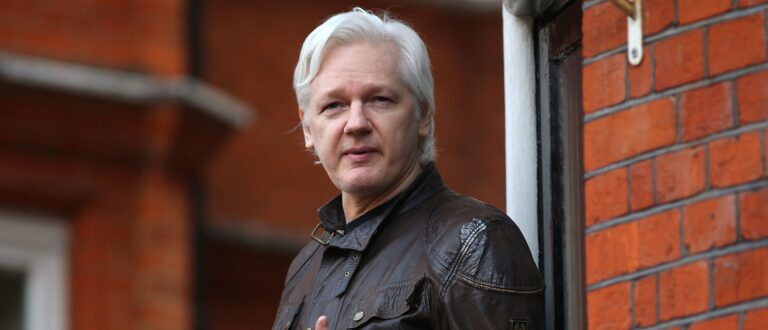

Sonia Sotomayor, one of the three remaining liberal Supreme Court justices, will turn 70 years old in June, is diabetic and had one parent who died at a young age. There are some offsetting factors at work — women live longer than men, and Sotomayor undoubtedly has access to world-class health care. So I’m not going to pull out an actuarial table or pretend to precisely estimate her lifespan. However, there is clearly a chance that Sotomayor will die or become unable to carry out her duties before Democrats again control both the presidency and the Senate.

I am not the only person to bring up this touchy subject. Josh Barro has been advocating for Sotomayor to retire. And the issue has reached the mainstream: Democratic Senators Richard Blumenthal and Sheldon Whitehouse have also not-so-subtly encouraged her to find the exit door.

However, I’m going to be more blunt than any of them. If you’re someone who even vaguely cares about progressive political outcomes — someone who would rather not see a 7-2 conservative majority on the Supreme Court even if you don’t agree with liberals on every issue— you should want Sotomayor to retire and be replaced by a younger liberal justice. And — here’s the mean part — if you don’t want that, you deserve what you get.

The nature of lifetime appointments to the Supreme Court — something I’d reform if for some strange reason I was tasked with rewriting the Constitution — is that we as citizens have not just the right but I’d argue the responsibility to think strategically about the justices’ age and health. Perhaps — perhaps — if the political class hadn’t seen such discussions as uncouth, Ruth Bader Ginsburg would have come under more peer pressure to retire when Barack Obama could have replaced her. Instead, of course, RBG died in the waning days of the 2020 presidential campaign, replaced on the bench by Donald Trump’s choice of Amy Coney Barrett.

As much as everyone with an interest in politics grasps that a Supreme Court seat is important, I suspect many people underestimate just how important. So let’s work through some math. I’m going to make a number of simplifying assumptions, but they ought to get us in the right ballpark.

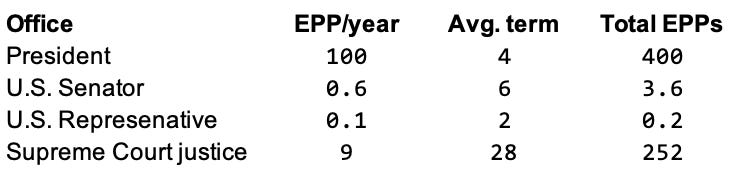

Let’s say that one year of a presidential term is worth 100 Electoral Power Points (EPPs). The number 100 is arbitrary; it’s just going to be a baseline for comparing the importance of the presidency to everything else.

Now let’s say that the legislative branch is as important as the presidency. Allocate 60 EPPs per year to the Senate and 40 to the House — the Senate is more important since it has the power to vote on judicial and cabinet appointments and on treaties. Divide the 60 points for the Senate points by 100 Senators; each year of a Senator’s term is worth 0.6 EPPs, therefore. And since there are 435 representatives, each year of a term in the U.S. House is worth about 0.1 EPPs.

And let’s give the judicial branch 100 EPPs as well. Allocate them 80 to the Supreme Court and 20 to various other lower federal courts; yes, that’s arbitrary — we’re just engaged in fairly blunt Fermi estimation here — but the nature of a hierarchical court system is that the highest court has most of the power since it can overturn lower court decisions. Divide those 80 points for SCOTUS by the 9 justices, which gets you to about 9 EPPs per year per justice.

Now let’s consider the length of the respective terms. A president serves for 4 years, a senator for 6, and a representative for 2. Meanwhile, the lifetime expected tenure for a Supreme Court justice is approaching 28 years (!) given increasing lifespans. So multiply each office’s yearly EPP score by the average tenure:

So winning the presidency is worth 400 EPPs. Winning an individual Senate seat is worth 3.6, and an individual House seat only 0.2 EPPs. A Supreme Court seat is worth 252 EPPs, by contrast, because there are only 9 justices and the terms last so long. That means a single SCOTUS seat is more than half as important as a 4-year presidential term!

Sure, you could quibble at the margins. Swing seats in the Senate and House arguably ought to count for more than noncompetitive ones. And presidents and senators determine who Supreme Court justices will be, so perhaps we should allocate more EPPs to them — then again, Supreme Court justices can determine rules for contesting elections and possibly even the outcomes of elections themselves. The point is this: a Supreme Court seat is really important. My previous newsletter concerned the process for allocating a single electoral vote in Nebraska, something that has a roughly 0.5 to 1 percent chance of determining the next president. In EPP terms, that works out to something like 400 x 0.75 = 3 EPPs. A Supreme Court seat is roughly 100 times more important than that!

To be fair, Sotomayor might eventually be replaced by another liberal justice even if she doesn’t step down now. But this year’s Senate map is very bad for Democrats — they’re almost certain to lose West Virginia, where Joe Manchin is retiring, and they’re under threat of losing Montana, Ohio, Arizona and Nevada, along with other states; meanwhile, their only real pickup opportunities are in Texas and maybe Florida, and both are stretches. Overall, prediction markets give Democrats only a 25 percent chance of keeping control of the Senate. Even if Joe Biden keeps the presidency, A GOP-run Senate allowing Democrats to appoint another liberal justice isn’t a proposition I’d want to bet on after they mothballed Merrick Garland.

And Democrats have to retain the presidency too, which is something of a 50/50 proposition according to these markets. (I’m overdue for an update on my own thoughts about the state of the presidential race, but the prediction markets — which have rebounded toward Biden in recent weeks — have come more into line with my views.) Now, these probabilities aren’t independent of one another: Democrats are much more likely to retain the Senate conditional upon Biden winning another term than they otherwise would be, in part because they’d still have VP Kamala Harris to break a 50-50 tie. Still, maybe the chances are something like 20 percent that Democrats control both the Senate and the presidency in January 2025. The odds are against them.

And after that? The 2026 Senate map contains reasonable pickup opportunities for both parties, and I’d guess whichever party wins the presidency this year will have a poor midterm given how unpopular both Trump and Biden are. So even if Democrats do retain the presidency and the Senate in 2024, they’ll probably lose the Senate in 2026; Sotomayor would have only a 2-year window and not a 4-year window to retire, in other words.

Now, if Trump wins the presidency in 2024 then Democrats will probably have a good midterm in 2026, and might have a fighting chance of regaining a trifecta in 2028. Still, this is awfully risky. The Senate has a built-in bias toward rural states, which is disadvantageous to the Democrats’ urban coalition. While I’m not much for long-term projections — political coalitions can change, and don’t underestimate the GOP’s ability to blow winnable Senate races by nominating wacky candidates — it could conceivably be many years before Sotomayor has another chance to retire and be replaced by another liberal.

In my forthcoming book, I go into a lot of detail about why the sorts of people who become interested in politics often have the opposite mentality of the world of high-stakes gamblers and risk-takers that the book describes. Both literal gambling like poker and professions that involve monetary risks like finance involve committing yourself to a probabilistic view of the world and seeking to maximize expected value. People who become interested in politics are usually interested for other reasons, by contrast. They think their party is on the Right Side of History and has the morally correct answers on the major questions of the day. And sure, they care about winning. But winning competes against a lot of other considerations like maintaining group cohesion or one’s stature within the group.

Nor do individuals usually have that much ability to influence political outcomes; even the act of voting is sometimes thought to be irrational. The feedback mechanisms in politics are also noisy; there’s only one presidential election every four years, and political outcomes are typically overdetermined — it’s hard to isolate one reason why a party wins or loses, and you can always tell yourself a story that suits your priors. Confirmation bias is a problem in every field — certainly including things like poker and finance — but politics is a cesspit for various sorts of cognitive biases.

So even though “rationality” is a loaded term, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say that you’ll encounter a lot of irrationality in politics. And I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say that the objections to replacing Sotomayor are irrational, too. One objection, for instance, is that we shouldn’t “force” the only Latina on the court to retire. Even if you endorse that sort of quota system, however, there is an obvious workaround: appoint one of the many other qualified Latino or Latina justices as her replacement; even if Hispanics are somewhat underrepresented on the bench, you only need to find one of them and there are a number of good options.

Another question is how moderate Democrats — particularly Manchin and Kirsten Sinema, who is also retiring — would feel about replacing a Supreme Court justice in an election year. But Republicans just did exactly that with Barrett. Manchin and Sinema, meanwhile, have generally been loyal to Biden on court appointments, both having voted for Ketanji Brown Jackson, for instance. And if need be, Sotomayor could make her retirement contingent on the confirmation of a suitable replacement.

You could also consider the knock-off effects on the presidential election, I suppose — would a Supreme Court fight hurt Biden’s re-election prospects somehow? Personally, I think the opposite is more likely to be the case — a fight would galvanize the Democratic base, particularly given that abortion tends to unite the party. But even if there are some downside risks for Biden, these ought to be compared against the gains from securing a Supreme Court seat, which considerably outweigh them.

So Sotomayor should retire. This is a much higher-stakes decision than nearly everything else I’ll discuss in the newsletter this year. And it is not a close call.

#Sonia #Sotomayors #retirement #political #test

+ There are no comments

Add yours