There’s something awful about a lost picture. Maybe it’s because of a disparity between your original hope and the result: you made the photograph because you intended to keep it, and now that intention—artistic, memorial, historical—is fugitive, on the run toward ends other than your own. The picture, gone forever, possibly revived by strange eyes, will never again mean quite what you thought it would.

“Here There Are Blueberries”—a new play at New York Theatre Workshop, conceived and directed by Moisés Kaufman and written by Kaufman and Amanda Gronich—begins with the discovery of a well-curated album of photographs. It’s not just one misplaced dispatch from a former world but whole pasted-together pages of them, carefully arranged in order to tell a story. The album was found in the nineteen-forties, after the Second World War, by a man who describes himself, more than sixty years later, as an “87 year old retired U.S. Lieutenant Colonel.” It’s the early two-thousands, and he’s sent a letter to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. The photographs are from Auschwitz.

“Blueberries” moves forward artfully, telling the true tale of the pictures and their march through public consciousness. The photographs show Nazis at ease at the site of the world’s most famous death machine. The Nazis lounge at a chalet, flirt with the secretarial pool, offer cheese smiles to the camera. None of the camp’s Jewish prisoners are pictured in the photographs, only their murderers, in the moments between murders. The album is a placid, subtly horrifying log of the mundane aspects of those people’s daily lives.

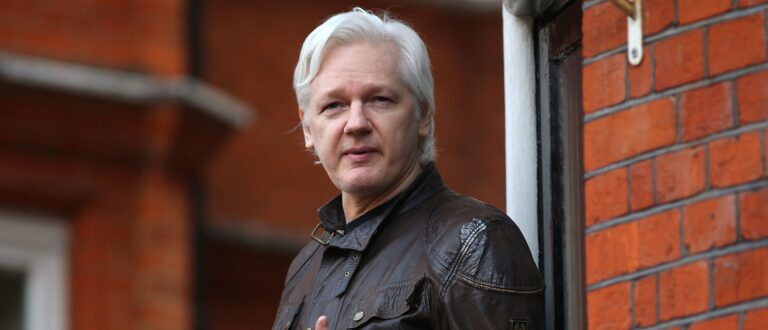

Rebecca Erbelding (Elizabeth Stahlmann), an archivist on whose desk the lieutenant colonel’s letter lands, recognizes the faces of notorious Nazis. There’s Josef Mengele, the so-called Angel of Death, and Rudolf Höss, the administrative architect of Auschwitz, “responsible for everything we think of as the camp: the barracks, the electrified fences, the guard towers, the extermination infrastructure . . . the whole organization.” After some detective work, Rebecca discovers that the album was apparently created by an upwardly mobile functionary named Karl Höcker. He probably put it together in a triumphal mood, thinking that it would be behind-the-scenes evidence of a heroic victory. Later, in the war’s aftermath, having lost the thing, maybe he thought of it compulsively, hoping it stayed lost, wishing he could have set it ablaze. The pictures—thirty-two pages of them, a hundred and sixteen images in all—had escaped his intentions not once but twice (so far).

Kaufman’s staging of the play is noble but simple. Characters approach the lip of the stage and state their thinking plainly. Besides Rebecca, there’s the director of the museum’s photography collection, Judy Cohen (Kathleen Chalfant, a brilliant performer whose mere presence gives the proceedings a fitting gravity), and the museum’s director, Sara Bloomfield (Erika Rose). The lighting, designed by David Lander, is bright and clean, just how we imagine the back rooms of a great museum might look (the apt scenic design is by Derek McLane), except when it dims a bit, the better to illuminate a picture from the album. Sometimes the flexible ensemble (which also includes Scott Barrow, Nemuna Ceesay, Noah Keyishian, Jonathan Raviv, Anna Shafer, Charlie Thurston, and Grant James Varjas) acts out a scene from a photograph—playing an accordion, laughing like schoolchildren on an exhilarating trip.

This is an institutional saga, the story of how a memorial museum—meant to honor and dramatize the lives of victims, not the idle pleasures of their captors—learned to metabolize Höcker’s difficult artifact. The play is based on real interviews conducted by Kaufman and Gronich, a documentary technique that Kaufman also employed for “The Laramie Project,” his renowned play about the death of Matthew Shepard. That method matches the art form that is this play’s spur: photography. Just like an interview, a photograph is a quivering, ambivalent, sometimes deceptive form of evidence, especially when the photographer is an amateur. You can suss out mood and tone, discern planetary facts like weather and time of day. But the spaces between exposures, before and after the questioning begins—who knows?

Even as “Blueberries” went about its business—it has the often dutiful tone of a high-quality PBS docuseries—I kept thinking about the lieutenant colonel who held on to the album for so many years, whose story the play must reasonably sweep past on the way to its forensics. In his initial letter to the museum, he says that he was sent to Germany to “do some work for the government.” What that work was he doesn’t specify. “While there,” he says, “I was housed in an abandoned apartment where I found a photo album. I salvaged the album and have kept it in my archives now for over sixty years.”

Sixty years! One wonders who, if anybody, he told of the record of horror living with him like a roommate in his home. How often did he look at it? How perfectly, over that span, had he memorized its faces, whether or not he was able—without a museum’s resources—to assign them any names? Why keep it for so long? What had he been thinking, at the outset and then for those many decades? That unknowable mystery, about the allure of evil and the power of photography, is sometimes captured by this play and sometimes not—a casualty, perhaps, of its fealty to pure fact.

One central concern of the play—what it means to look at the mundane when, somewhere just beyond the frame, there’s a massacre afoot—makes it a kind of companion piece to “The Zone of Interest,” the recent Oscar-winning film by Jonathan Glazer, very loosely adapted from the novel by Martin Amis. The movie tracks the home life of Rudolf Höss, the administrator who, with his distinct high-and-tight haircut, slick and floppy up top, recurs throughout the Höcker album. “The Zone of Interest” uses sound design—the crackle of flame, cries coming from invisible mouths—to create an underhum of terror, to make an unseen context the whole point of the domesticity that shows up onscreen. “Blueberries” makes that irony a clear pain point. The museum’s staff worry about showing the photographs, but eventually, and rightly, decide that there’s no way not to. To understand sickness like this, you need to see how the perpetrators are—in more ways than you might like—just like you.

Blood underpaints today’s world, too, no matter how many lovelier colors fill our normal days. You go about your business; attend meetings on Zoom or at some office; ride the subway and watch the faces, with their plural origins, blur past; take walks through the warming spring air, admiring the onrushing green. Now and again, you look down at your phone, and here come the images: a bloody limb, a shell-shocked parent, a dead child caked in rubble and dust. Photographic evidence, the irrefutable cinematography of the smartphone amid emergency, death in vivid hue: this is how we know that things are wrong.

There is no leisure in these newer images, no blueberries and cream eaten by smiling accessories to a heinous passage in history—just the news, seemingly simultaneous with its happening. I sometimes wonder if these images and videos, for now fleeting on screens, illustrations on a scrollable feed, will one day adorn the walls of museums, or whichever repositories the people of the future choose for the display of their collective glories and great shames.

Auschwitz and the other camps whose names haunt our textbooks were mysteries to outsiders—this was part of their power. It took so many efforts of reconstruction like the one dramatized by “Here There Are Blueberries” just to know, belatedly, what exactly went on. Photography will also be part of the story of today’s traumas, but in a very different way. We won’t be able to say we didn’t see. ♦

#Chilling #Truth #Pictured #Blueberries

+ There are no comments

Add yours